Tuesday, December 18, 2007

in the beginning: a study in grammatical time

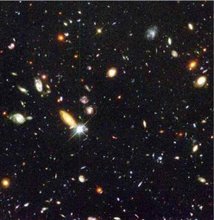

This is the story about the beginning of the stars, except there really was no beginning so to speak, at least not in the way that we say beginning, because that would imply that time existed before time existed, which it could have, semantically speaking—I mean, we could ask, “What was there before time began?” but this logical lexography just can’t hold up to empirical evidence, which is to say, it was more like a non-beginning with a lot of stuff going on all at once, but the stuff wasn’t there before in the same way that it was there after the big non-beginning of the beginning of the stars and then stars were born, and from star dust, on a molecular level, your hands, my eyes, this page, these words.

Part Two: The Short Version

This is the story about the beginning of the stars. There really was no beginning, so to speak. At least not in the way we say beginning. That would imply that time existed before time existed. It could have existed, semantically speaking. We can ask, “What was there before time began?” But this logical lexography leads nowhere. It just can’t hold up to empirical evidence. In other words, it was more like a non-beginning. But there was a lot of stuff going on. And everything was happening at one time. But the stuff before was different from the stuff after. After the big non-beginning of the beginning, stars were born. And from star dust came hands, eyes, words, this page.

Thursday, August 30, 2007

a brief history

I like relativity and quantum theories

because I don’t understand them

and they make me feel as if space shifted about like a swan that

can’t settle,

refusing to sit still and be measured;

and as if the atom were an impulsive thing

always changing its mind.

~ D. H. Lawrence

I have a Swiss cheese kind of science background—substantially rich in some places, holes in other places. Explain why a clock ticks faster as it nears the event horizon, no problem; add numbers larger than the amount of fingers I have, that’s asking a lot. Bifurcate a logistic equation, sure; multiply fractions . . . I have no idea how to multiply fractions.

Among the many and varied causes of this Swiss discrepancy are two major contributors: The first is the jerk who sat behind me in 7th grade math class. Jerk put bugs in my hair unbeknownst to me until sometime toward the end of class when the bugs migrated from my head and commenced roaming the rest of my topography. The discomfort caused by the insects was negligent compared to the devastating humiliation caused by sneering, pointing peers, so, I never went back. Hence, a mathematical education that does not exceed the 7th grade level, and, holes. I quit going to the rest of my classes shortly thereafter, having concluded that school was for learning about humiliation, fear, and self-loathing, and not where I could learn about what makes clouds look the way they do or how those rings around Saturn got there in the first place. A few bad years and a lot of dangerous substances later, I re-entered school as high school student, where I met the second major contributor.

Pete taught science classes at the alternative high school I attended, introduced me to what would become an insatiable, absorbing passion for scientific understanding, and saved my life. I was fortunate enough to attend Pete’s Space Science class where I discovered that I was not stupid, just miseducated, and that science, more than anything else, yielded the most satisfactory answers to my insufferable and growing tower of mostly unanswerable questions. Thus began some filling in of the empty spaces.

I became addicted to Scientific American. I read Asimov, Feynman, Hawking, Gribbin, and Davies. I read about atoms, relativity, quantum theories, chaos theories, Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, the paradox of self-referential systems, history of science, and philosophy of science. I even received a [fancy tech school] “Medal of Achievement in Math and Science” and a small scholarship because the admissions committee assumed I had the mathematical qualifications due to the high level of promise I demonstrated in my science classes.

In college I took all the chemistry, physics, astronomy, biology, and botany classes I could take without calculus prerequisites and taught myself the math I needed on a case by case basis. I am in love with covalent bonding, I dream chemical reactions, and I have a veritable encyclopedia of astronomical and botanical lore and nomenclature stored in my brain.

When I enrolled in college for the first time (a long time ago), I fully intended to be a Physics major and go on to become a Professor of Physics. I registered for pre-algebra three times and finally passed on the fourth try. I was yet undaunted and still cultivated dreams of theoretical physics notoriety. I would say that naivety is the mother of courage. During the subsequent decade of my on-again-off-again college career I would register and withdraw from college algebra more times than I have fingers. However, because I understand now that learning mathematics requires a step ladder process, and I could not seem to leap up even to the bottom rung, I finally gave up trying to take college algebra—bye-bye Physics major, hello Arts and Letters.

I still want to become a Physics Professor. I took Complexity in the Universe I with the noted physicist Dr. Semura and more than once he suggested I become a Physics Professor. I take this to be the greatest compliment I have/will ever receive in my life-time. I followed up with Complexity in the Universe II and discovered that I really enjoy writing science based, big questions, what-does-it-all-mean-reflection stuff. So, what does an Arts and Letters major who loves science but can’t add, and who loves writing but wants a steady income, grow up to be? A restaurant manager. An art school applicant. An avid “science for the lay person” reader. And maybe, someday, a poet.

Thursday, August 23, 2007

letting go: a lesson in resumptive modifiers

So this is the way it comes down, she thought, heavily.

So with the night fallen to its knees all around her, and stars exploding, she resolved to finally pick up some of the pieces of the day, pieces that had broken up and scattered themselves years ago in the pallid litter of a languishing room. But beneath the unbearable dark, her hands were hers, were responsible for letting go of the rope, were gathering shards of light and slivers of remembrance.

She searched for solace. She searched for some consolation.

She sought string and tail feathers in the ruble and promised to fashion a proper kite, a kite that was tangible enough to pull the night up off its knees, and fly through the prevailing headwinds, trailing the heft of time behind it.

Wings.

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

the orrery

the planets go, the planets go

without a sound. Without a sound,

the planets go, the planets go

round and round.

Round and round

the moon circles, the moon circles

without a sound. Without a sound,

the moon circles, the moon circles

round and round.

Round and round

the sun spins, the sun spins

without a sound. Without a sound,

the sun spins, the sun spins

round and round.

Round and round

the planets go, the planets go

without a sound. Without a sound,

the planets go, the planets go

round and round.

Friday, August 10, 2007

senior thesis: not sure if this even remotely answers the question

The idea is simple: Save the rainforests. The only way to save the rainforests is to find something that the world will recognize as a valuable commodity and sell it, without destroying the forests in the process. Medicine yields an extremely high return on investment and can be extracted from the vegetation with minimal impact. And everyone in the world needs medicine. So the really interesting thing about plant medicine from the rainforest is that the indigenous rainforest people are the experts. And the really interesting thing about indigenous rainforest people is, well, everything; not the least is a perception of reality that is completely foreign to a poor girl with a questionable education.

So, one discipline led to the next in my quest to become The Best Ethnobotanist in the World: Biology led to chemistry led to physics led to astronomy led to logic led to philosophy, etc. And on the Arts side, anthropology led to politics led to language led to literature led to writing. . . Throw in a bunch of full time jobs, a couple moves across the country, military service, marriage, divorce, and a life-time of debt, and all this culminates in a Bachelor of Arts in Arts and Letters.

So what can be said about the perceptual lens of my discipline? My “discipline” came about haphazardly as a result of the desire to protect what I love. Throughout my studies I have encountered obstacles and opposition, but the original intent is still intact. I will graduate with a BA in BS, failed attempts, hard feelings, no math skills, my goals unreached and ultimately unattainable, but I still want to save the rainforests. And I know just how many disciplines it may take to reach the world.

Monday, July 30, 2007

paul thinks the moon is boring

O cold marred magma, O turning pitted gibbous!

Your elliptical eccentricity, your diurnal libration,

Is strikingly inconsequential

To our insipid imagination.

I was first introduced to astronomy when my father told me to walk in a circle around a small fern to demonstrate how we see the phases of the moon from Earth. This was the most incredible thing I had discovered in my four years on this planet, and the only thing to trump the small green lizards whose tails came off in my hands and then grew back again.

Two years later my father built his own telescope in our attic. He even ground his own lens. That was a couple decades ago, but I can still recall the smell of whatever the sticky-smooth, orangish substance was that he used to polish the glass.

Then I saw the rings of Saturn. They were really out there, just like all the books said they would be. What about Pluto? Or comets? Were they really out there, too? And how did those rings around Saturn get there anyway? And why are there craters on the moon? I remember believing then that all the answers were already known, and that all I had to do was read enough books in order to discover them. This belief soon proved false, but not before I had come across enough unanswerable questions to lead me to General Relativity at a relatively young age.

For some reason, the notion of gravity as a consequence of the curvature of space-time was much easier for me to grasp, and a lot more interesting, than some other more fundamental concepts immediately applicable to life. Fractions, for example, were completely lost on me, as was the generally agreed upon notion that science was not cool and MTV was. Even now, I can’t add fractions, or dress the fashion, but I can explain why a clock would tick faster as it approaches the event horizon.

And even though I’ve been thinking about the fabric of space-time and event horizons for longer than some of my classmates have been alive, I still find the subject matter infinitely fascinating. In fact, I don’t know what could be more fascinating than an impossible-to-ponder-all-the-possibilities universe right outside our window—except, maybe, those tiny tail-falls-off-and-grows-back-again lizards.

So, speaking of infinitely fascinating subject matter, I was shocked to hear a friend of mine say recently, “The moon is so boring, it would be better if we could project movies on it . . . or something.” I do realize that I am a prisoner of my own perception paradigm, but even so, it had never occurred to me before that someone might find the moon to be a boring thing. To my way of seeing things, this was blasphemy, absurd, and untrue. All my wonder, curiosity, passion for science, appreciation of the natural world—my solace within the confines of unnatural surroundings—it all began with the phases of the moon. When I look up at the glowing, pitted gibbous today, I am no less astounded than I was when I was four.

I felt sad for my friend and for our closest lunar relative. I wondered what it would be like to be a prisoner of a perception paradigm that did not include moon-magic. Was Saturn boring too? The constellations? I felt like I was in sixth grade again, when all the kids thought that I was boring, and I thought, Sometimes I am more at home in the universe than I am among my own peers.

Friday, July 20, 2007

on the scale of things, relatively speaking

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stares—on stars where no human race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

~Robert Frost

Which is more vast and complex: the universe or the human experience of it? I never can decide. I imagine that this would be easier to determine if we had a highly sensitive vastnesscope with which to detect the average vastness absorption spectra of any given system—lots of blue in that open-system universe, some yellow showing up in that closed minded individual. A complexity scale would come in handy, too. How complex is the universe? Oh, it weighs in at about 257 VLU (very large units), that’s a little bit more than a medium sized orange, and a little bit less than my cat.

Now that I think about it, what I really need is an unfathometer so I could ask, “Hey, Todd, how unfathomable is the night sky?” And Todd could answer within a 5° ± accuracy range, “Well, seems to be about 81° RU (ridiculously unfathomable)." Of course my next question would be, “Hey, Todd, how unfathomable am I?” And Todd would tell me to place the unfathometer under my tongue for six to eight minutes to get a good reading. I presume I am a great deal unfathomable, but then, so are cypress trees and leaf-cutter ants. Which makes me wonder, Is insignificance scale invariant?

Recently, my cosmic imagination has been stuck in a scale invariant rut. All the usual late night ruminations about vastness, complexity, and other such unfathomable things, eventually wind up falling into my scale invariance memory basin. I think this is because the relation between scale invariance and fractional dimensionality puts a significant twist in the paradox of nondenumerable infinity and seems to lead to the satisfactory conclusion that, indeed, something can come from nothing. This is a very big thing, as far as I can tell, since apparently the coming into existence of the entire universe rests on this single, difficult-to-accept concept.

Also, it seems to me that some species of information may be scale invariant, and depending on what form the scale invariant information takes on, or more accurately, what kind and how many quantum particles the information is made of, I think it’s possible that the universe could have been planning on me for the last 13.7 or so billion years. Not that this would make me any more significant than the onion I chopped up and put on my pizza; the universe would have had to have been planning on that onion too, and this I must concede if I am to be a non-discriminating scale invariant information theory maker-upper.

So the real stickler is that even if I’m right about this whole S.I.I.T (scale invariant information theory) thing, which may have absolutely no scientific basis whatsoever but it’s my imagination so I can make up whatever I want, I still come around to the inevitable question of significance. The reality of my own insignificance on the universal scale is something that used to bother me a lot as a kid. Perhaps this early, intimate familiarity with ultimate futility is what compelled me to begin questioning the nature of the universe, and human experience, in the first place.

Today, however, I have learned to reconcile the knowledge of my insignificance on the universal scale with the understanding of my significance on a much smaller scale. Namely, the one that consists of me, myself, and my cats. I love my cats, and to them I am rescuer, food giver, care taker, pooper scooper, adopted mother, and basically god. That’s significant enough for me to sleep at night. After, of course, I contemplate vastness and complexity, the human experience of the universe, and the necessity of an unfathometer.

Monday, April 16, 2007

what i don't know

Flower in the crannied wall,

I pluck you out of the crannies,

I hold you here, root and all, in my hand,

Little flower—but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is.~Alfred, Lord Tennyson

What I don’t know about the universe and what I would like to know about the universe is the same thing: Why does it exist?

To me, why the universe, humans, consciousness, and even I, all exist is the most compelling inquiry. It is also maddeningly the most elusive. But how can we claim to know anything if we don’t even know why we know it? Don’t get me wrong, I’m glad to find out all the answers I can; it’s like putting a billion piece puzzle together. The only problem with the cosmic puzzle is that even if I could put most of the pieces in their respective places during my lifetime, the whole picture would never emerge because of the One Missing Piece: Why.

We've learned a great deal about how our universe exists by measuring and calculating a many number of things, and, to some extent, what exists in our universe through quantifiable observations. The when seems to be accounted for, but then, do we really understand the nature of time well enough to derive a finite number from a possibly infinite set of circumstances?

In commenting on the age of the universe we inevitably find ourselves in a bit of a conundrum because if we say that the universe is about 13.7 billion years old, what we are implying, semantically and literally, is that there was a point in time when the universe was one second old.

This logical lexography gives rise to the Heap paradox and we may ask, “What was going on one second before that second when the universe was one second old, and before that second before that second?” ad infinitum. The real clincher is that if time did not begin until the universe began, then it makes no sense to ask, “What happened before time began?” but this is, nonetheless, precisely what I what I want to ask.

I come to cosmology with the same fascination and reverence I have devoted to the study of botany. Thrilled by the language involved, learning the technical details, and gaining a more meaningful understanding of the world around me, I never tire of hearing the words dark energy or cotyledon.

At the same time, I realize that I can learn all about big bang theory, expanding space, photosynthesis, and how growth comes from meristematic tissue, but will anyone ever know why a flower grows?