O cold marred magma, O turning pitted gibbous!

Your elliptical eccentricity, your diurnal libration,

Is strikingly inconsequential

To our insipid imagination.

I was first introduced to astronomy when my father told me to walk in a circle around a small fern to demonstrate how we see the phases of the moon from Earth. This was the most incredible thing I had discovered in my four years on this planet, and the only thing to trump the small green lizards whose tails came off in my hands and then grew back again.

Two years later my father built his own telescope in our attic. He even ground his own lens. That was a couple decades ago, but I can still recall the smell of whatever the sticky-smooth, orangish substance was that he used to polish the glass.

Then I saw the rings of Saturn. They were really out there, just like all the books said they would be. What about Pluto? Or comets? Were they really out there, too? And how did those rings around Saturn get there anyway? And why are there craters on the moon? I remember believing then that all the answers were already known, and that all I had to do was read enough books in order to discover them. This belief soon proved false, but not before I had come across enough unanswerable questions to lead me to General Relativity at a relatively young age.

For some reason, the notion of gravity as a consequence of the curvature of space-time was much easier for me to grasp, and a lot more interesting, than some other more fundamental concepts immediately applicable to life. Fractions, for example, were completely lost on me, as was the generally agreed upon notion that science was not cool and MTV was. Even now, I can’t add fractions, or dress the fashion, but I can explain why a clock would tick faster as it approaches the event horizon.

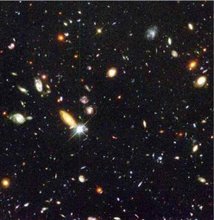

And even though I’ve been thinking about the fabric of space-time and event horizons for longer than some of my classmates have been alive, I still find the subject matter infinitely fascinating. In fact, I don’t know what could be more fascinating than an impossible-to-ponder-all-the-possibilities universe right outside our window—except, maybe, those tiny tail-falls-off-and-grows-back-again lizards.

So, speaking of infinitely fascinating subject matter, I was shocked to hear a friend of mine say recently, “The moon is so boring, it would be better if we could project movies on it . . . or something.” I do realize that I am a prisoner of my own perception paradigm, but even so, it had never occurred to me before that someone might find the moon to be a boring thing. To my way of seeing things, this was blasphemy, absurd, and untrue. All my wonder, curiosity, passion for science, appreciation of the natural world—my solace within the confines of unnatural surroundings—it all began with the phases of the moon. When I look up at the glowing, pitted gibbous today, I am no less astounded than I was when I was four.

I felt sad for my friend and for our closest lunar relative. I wondered what it would be like to be a prisoner of a perception paradigm that did not include moon-magic. Was Saturn boring too? The constellations? I felt like I was in sixth grade again, when all the kids thought that I was boring, and I thought, Sometimes I am more at home in the universe than I am among my own peers.